Professionals

Welcome to the Professionals pages

Welcome to the LSCP Professionals pages. Here you will find key information, resources and links to support you in work to safeguard children.

Visit our Partnership Learning tab to find out about courses and learning events available to you

Have you seen the latest LSCP Safeguarding Briefing?

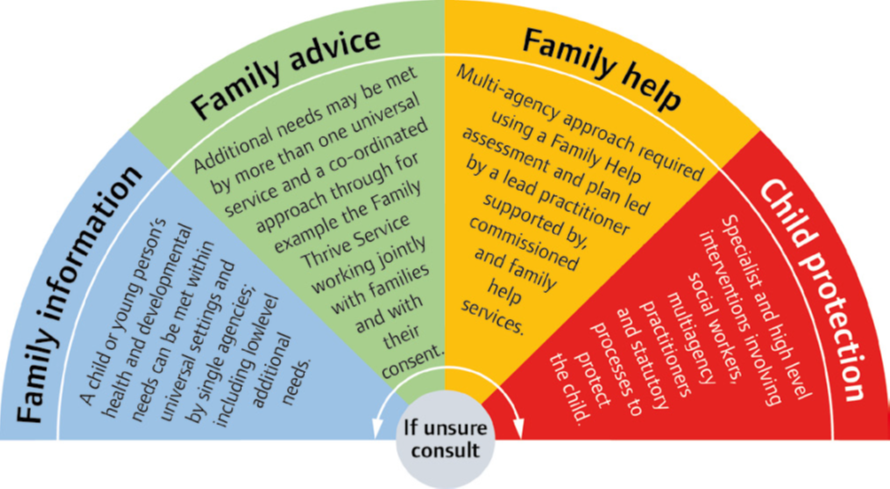

LSCP Family Help Continuum of Need (2024-25)

This document has been updated from October 2024 in line with the DfE Families First Pathfinder which sets out our approach to keeping children safe and protected, and underpins our local vision to provide the right support at the right time for children and families in Lewisham, at the earliest opportunity. This document is aligned to the London Safeguarding Children: Threshold Document: Continuum of Help and Support; however our language and terminology in Lewisham has been reframed as we develop our Family Help offer.

In Lewisham we know that the majority of children, young people and their families can be supported through a range of universal services. These services include education, early years, health, housing, and services provided by voluntary organisations. These services include education, early

years, health, housing, and services provided by voluntary organisations. However, some children have more complex needs and may require access to Family Help to support them. We want to ensure that we provide the right help and support for families which is led by the presenting need and not a prescribed framework. We understand the need to be flexible and have adaptable responses to how we with work with families.

This document provides an overview to support all professionals and agencies who work with children and young people, from or in the Borough of Lewisham, to identify when help or protection is needed through families lives. Its purpose is to develop shared guidance and understanding that sets out the local partnership arrangements for the planning and provision of services.

The document should be read alongside statutory guidance outlined in the London Safeguarding Children Partnership Threshold - Continuum of Need Matrix to consider specific indicators.

NB. Agencies in the London Borough of Lewisham should also comply with additional LSCP local protocols and practice guidance that are published on the LSCP website.

LSCP Family Help Continuum of Need 2024-2025

LSCP Family Help Continuum- Key Summary 2024

Prevention and Family Advice

Our vision for our Prevention and Family Advice offer is for children and young people in Lewisham to thrive, reaching their full potential and able to take full advantage of the opportunities available to them in Lewisham, London and beyond.'

Prevention and Family Advice offer describes support available to children, young people and families up to the level of statutory or specialist intervention. It is there to support from pre-natal stages up to the age of 18 years (25 years for those with SEND). It includes information and advice, universal services, open access services and more tailored support for children, young people, and families.

‘Working together to safeguard children’ (2023) is the statutory guidance which details the vital role of effective early help intervention for children at risk of poorer outcomes. It emphasises that all agencies have a collective responsibility, to identify, assess and provide effective prevention and advice services. Our LSCP Family Help Continuum of Need Document will help you assess the level of support needed or risks present. Professionals should refer to the continuum of need document before making a FFCP request.

Within our Prevention and Family Advice offer there are both information and advice services. These services work together, ensuring the most relevant and focused plans and interventions are in place:

- Family Information are services that all children and families can access (for example, Family Hubs, Children Centres, GPs, Schools, Early Years, Community organisations etc.)

- Family Advice are services for children and families that have multiple needs which require a multi-agency intervention (for example, Family Thrive). The Families First Contact Point (FFCP) is the single point of entry for referrals to Lewisham’s Family Thrive Service.

Family Thrive

Family Thrive is a consent based Family Advice Service.

Family Thrive works with families who have children aged 0 to 18 years, (and up to 25 years for SEND) who may require tailored parenting support to help them be happier and healthier. We work closely with schools and other professionals with consent. Consent from the parents/carers must be gained at the point of referral.

Family Practitioners undertake a Family Advice Record & Plan, and develop outcome-focused plans in line with Signs of Safety and in a way that promotes holistic and family led planning

The Family Practitioner is the lead professional and work alongside partner agencies as part of the multidisciplinary Team Around the Family and provide tailored parenting support and undertake direct work with children and young people.

Parenting Support

Instances where there is low level or emerging concerns might result in referrals to the Prevention & Family Advice service for tailored parenting support from the Family Thrive Service. Skilled Family Practitioners will undertake focused family based interventions for a fixed period of time working with parents to sustain positive parenting practices and ensure all appropriate support needs are provided.

Parents can also attend any of Lewisham’s Family Hubs for support, advice and access to parenting support such as:

Family Navigators

You can talk to one of our Family Navigators who are based in our Family Hubs offering free, confidential and non-judgmental support if you are a parent or carer living in Lewisham.

Owl Babies Course

During this course we share ideas, talk about the challenges of being a parent, support mental and emotional wellbeing using Five to Thrive, Nature and the outdoor environment.

Baby Massage

Our baby massage courses aim to support your bond with your baby through easy to learn, gentle and positive movements whilst enjoying relaxing and special one to one time together.

Triple P for Babies

Triple P for Baby programme aims to prepare parents for a positive transition to parenthood and the first year with baby, promoting sensitive and responsive care in the perinatal period

Staying Healthy

At Lewisham Family Hubs Families can sign up for and collect FREE Vitamin D and attend Weaning and Healthy Eating Sessions and Courses.

These include:

- Starting Solids

- Portion Sizes

- Fussy Eating

Visit www.lewishamfamilyhubs.org for more information, timetables and details of Family Hub locations

Non-Violent Resistance-Informed Parenting Programme

- The programme is aimed at parents and carers of pre-teen children (aged 8 years and over) experiencing challenging/violent and extreme behaviours.

- NVR is a concept that draws inspiration from those who have sought to bring about changes in society in a non violent manner.

- The programme offers a series of tools and techniques to support parents and carers of children and young people who display challenging attitudes and behaviours.

- Parents are guided through a set of core principles based on the idea of carefully planned actions to help support the management of challenging behaviour.

Triple P (Positive Parenting Programme)

- Positive Parenting Programme, is a broad-based parenting programme for parents and carers of children aged between 2-10yrs who are struggling to manage aspects of their children’s behaviour.

- The programme is 6 to 8 weeks long made up of 4 mandatory classroom sessions between 2 and 4 individualised 1:1 sessions.

Children Overcoming Domestic Abuse (CODA)

- CODA is a twelve-week recovery intervention for mothers and their children who have experienced domestic abuse. We are currently delivering to children in Years 3 and 4.

- Running concurrently, CODA provides two-hour sessions for mothers and their children on a weekly basis. Each week covers a specific theme and programmes are divided into age appropriate groups. Note: siblings cannot access the same group.

- CODA seeks to support the recovery process and aims to:

- Validate the children’s experiences

- Reduce the self-blame that is commonly associated with children experiencing abuse

- Develop a child-appropriate safety plan

- Manage emotions appropriately

- Enhance the mother-child relationship

- Enable both the mother and child to heal together

The Juniper Programme

- The Juniper Programme has the same aims as the CODA Programme but is delivered to children under the age of four years and the adult survivor.

More information on all Family Hubs service can be found at www.lewishamfamilyhubs.org.uk.

Families First Contact Point (FFCP)

What is the FFCP?

The Families First Contact Point (FFCP) (formerly known as the Multi-Agency Safeguarding Hub - MASH) provides a single point of access to the services that help keep children safe. It is a multi-agency team made up of representatives from a range of services that provide advice, support and protection as needed. These services include:

Family First Contact Point (FFCP)

Allegations Against Professionals (LADO)

Making a referral to the Local Authority Designated Officer and Possible Outcomes

The LADO (Local Authority Designated Officer) provides advice and guidance to employers and other individuals/organisations who have concerns relating to an adult who works with children and young people (including volunteers, agency staff and foster carers) or who is in a position of authority and having regular contact with children (e.g. religious leaders or school governors).

There may be concerns about workers who have:

- behaved in a way that has harmed or may have harmed a child

- possibly committed a criminal offence against or related to a child

- Behaved towards a child or children in a way that indicates they may pose a risk of harm to children;

- behaved towards a child, or behaved in other ways that suggests they may be unsuitable to work with children

What should be referred to the LADO?

Any concern that meets the criteria above should be referred. Initially it may be unclear how serious the allegation is. If there's any doubt, the LADO or the designated safeguarding lead person in your agency should be contacted for advice.

What the LADO does:

The first step will be to offer an initial consultation about the concern. This may consist of advice and guidance regarding the most appropriate way of managing the allegation. The LADO will:

- help establish what the 'next steps' should be in terms of investigating the matter further

- liaise with the police and other agencies, and arrange for an allegations meeting to be held if required; if the case is complex there may be a series of meetings

- monitor and maintain an overview of cases which meet threshold to ensure they're dealt with as quickly as possible, consistent with a thorough and fair process

- ensure child protection procedures are initiated where the child is considered to be at risk of significant harm

- ensure the appropriate agencies are involved in the investigation

- ensure advice is provided in relation to the adults remaining in post over the course of the investigation

- ensure issues of sharing information with parents and other relevant individuals are considered

- assist an employer in decisions about a person's suitability to remain in the children's workforce, and whether a referral should be made to the Disclosure and Barring Service (DBS) or the appropriate regulatory or professional body

- In cases where the adult is unaware of the concern or allegation, it may not be appropriate to tell them immediately and may prejudice a potential police investigation. The LADO will provide advice.

Outcomes

The outcomes from a LADO referral may include:

- finding that the allegation is malicious

- finding that the allegation is unsubstantiated

- finding that the allegation is substantiated

- finding that the allegation is false

- finding that the allegation is unfounded

- internal investigation by the employer including consideration of disciplinary procedures

- a police investigation

- police prosecution

- Where the adult is reinstated there may be recommendations in relation to additional support, monitoring or training.

- Where an individual is dismissed from their post, a referral must be made to the DBS which makes decisions on whether individuals should be barred from working with children.

- Compromise agreements are not an acceptable resolution to a concern, and even if someone resigns it should not prevent a full and thorough investigation into the matter.

LADO Procedure & Protocol - 2023

To make a referral to the Local Authority Designated Officer (LADO), please email a LADO Contact & Referral Form to LewishamLADO@Lewisham.gov.uk.

Named Lewisham LADO:

Eleanor Hargadon-Lowe, London Borough of Lewisham, 1st Floor Laurence House, 1 Catford Road, SE6 4RU

There is also a Deputy LADO system, as such you may speak with and be supported by a member of the team.

LADO Voicemail service: 020 8314 7280. Please note this is a manned voicemail, so please leave a clear message and the LADO or Deputy LADO will respond to you as soon as possible within 24 hours.

LADO Annual Reports

LADO Annual Report 2023-2024

LADO Annual Report 2022-2023

Useful Links

London Safeguarding Children Procedures

London Safeguarding Children's Partnership

Working Together to Safeguard Children 2023

Keeping Children Safe in Education 2023

Child Not Brought to Appointments

The following animation is aimed at raising awareness about the consequences of missing appointments and to ensure that children and adults get the medical care that they need. This is a powerful reminder that children do not take themselves to appointments, and for practitioners to reflect on the impact of missed appointments on a child's wellbeing. With thanks to Nottingham City CCG & Safeguarding Children Partnership.

Definitions:

Child Not Brought (CNB): Child was not brought to the appointment without cancellation.

Did Not Attend (DNA): Did not attend appointment without cancellation

No Access Visit (NAV): Not available at home to be seen for appointment.

Background

It is recognised that many children miss appointments in hospital and community settings, and are not available at home to be seen by staff working in different agencies.

Many Serious Child Safeguarding Practice Reviews (Serious Case Reviews) / Homicide Reviews both nationally and regionally have featured CNB, DNA and NAV as a precursor to serious child abuse and child death.

Key principles for Practice

Organisations

- All agencies should have a policy and local guidance for managing CNB, DNA and NAVs which underpins both process and practice and reflects the differing needs of children and their families.

- Services provided should be child and young person friendly and work in partnership with parents and other practitioners.

Practitioners

- Practitioners should be child focussed and consider children and young people even when the CNB / DNA / NAV relates to the parent/carer, particularly when mental health or problematic substance misuse is featured.

- Practitioners should ensure they are appropriately trained in the identification of child maltreatment to ensure effective judgements are made as to whether the child or young person’s health and development are subject to impairment.

- Develop robust communication links with parents and other professionals or agencies working with the child and ensure that any outcome or consequence for the child or young person is explained.

- Know when and with whom to share information when there are concerns about a child or young person’s welfare and where to get advice.

- Document assessments, analysis, communications and actions taken in the child / young person or parent / carer record as relevant.

- Parents / Carers may disengage with any agencies caring for themselves or their children.

- Remember disengagement is a key risk factor for children and families and may be a precursor to something more serious happening.

Managing CNB/DNA/NAV

Assessment

- Following CNB / DNA / NAV the responsibility for any assessment of the situation rests with the practitioner to whom the child has been referred in conjunction with the referrer (Laming 2003).

- Consider the needs of the child and the parents / carers capacity to meet those needs.

- Consider environmental context of the child’s situation.

- Identify whether intervention is required to secure a child’s welfare.

Communication

- Verbal / written communication with the parents / referrer needs to outline consequence of CNB / DNA / NAV on the child.

- Where there are clear child protection concerns, discuss these with your line manager and make a referral to the Multi-Agency Safeguarding Hub (MASH) mashagency@lewisham.gov.uk in accordance with Lewisham’s procedures.

- Where there are concerns relating to children, information should be shared with the Line Manager, Named or Designated Safeguarding Lead / Lead Professional or other agency working with the family who can add to the information sharing process.

Record Keeping

- The content of discussions should be clearly documented along with any actions and outcomes in the child or parent / carer record.

- Analysis and conclusion should also be documented ensuring that any referral letters and context of previous records have been considered.

Action

- Consider arranging another appointment, check addresses and other details for accuracy.

- Ensure parents / carers are informed about the consequence(s) of further non-attendance for the child / young person and with whom information will be shared with should there be further CNB / DNA / NAV.

- Repeated CNB / DNA / NAV should result in a Team Around the Family (TAF) meeting to agree the best course of action.

- Unless there is a concern that a child / young person is likely to suffer significant harm then a referral should not be made to MASH until it is established the TAF has not worked. The referral will need to show what work has been attempted, by whom, and what is expected a referral to MASH will achieve.

- An immediate referral to MASH should be made if it is established urgent medical attention has not been sought or delayed for a child or young person by a parent / carer.

Audit

- Agencies should find ways to collect information in respect of CNB / DNA / NAV to increase the uptake of services in order to safeguard children and young people and improve their outcomes.

Audit Suggestions

- Number of services CNB / DNA / NAVs under the age of 18 and include the outcome.

- Number of service CNB / DNA for mental health, drug and alcohol services including outcomes of the CNB / DNA.

- Number of NAVs including outcome of no access (all services).

- GP’s should audit outcomes of CNB / DNA / NAV and consider the consequence of non-engagement in order to work with families to improve engagement.

Additional Policies

L&G NHS Trust – Child Was Not Brought / No Access Visit Policy December 2019

Useful Websites

www.london safeguarding children partnership.gov.uk

www.everychildmatters.gov.uk

Child Protection Conferences

Reports

The London Borough of Lewisham Multi-Agency Child Protection Conference Report Template was introduced in February 2022.

ALL professional agencies must complete this report, even if they are unable to attend but are invited. This must be sent to the Quality Improvement Business Support Team (QISBusinessSupport@lewisham.gov.uk) within the following timescales:

- Initial Child Protection Conference – 2 working days before

- Review Child Protection Conference - 5 working days before

These reports must be shared with the families before the meeting – there should not be any information that the family do not know that will be shared in the meeting. If there is confidential information that cannot be shared with the family in the conference due to concerns that this will increase risk to children, then please alert the Chair to this before the meeting.

Structure of the Conference

The Conference is chaired by a Child Protection Chairperson, who is a qualified and experienced social work professional. Their responsibility in the meeting is to make decisions in respect of the level of risk faced by a child, and create a multi-agency plan that aims to keep the child safe.

The chair will endeavour to gather information (not already provided in the reports) and seek to focus on the key areas of risk/ harm to the child, and any examples or times where the risk has been managed and the child kept safe (this is called existing safety).

The Chair will speak with everyone in the conference to gather their views and analysis, as well as recommendation (see below).

Participation in the Conference

All relevant professionals who are involved with a child or their family are requested to attend a Child Protection Conference. The focus in the meeting will be around analysis of the harm and safety and what plan needs to be in place to address the key areas of danger and risk.

It is really important for professionals to keep their summaries brief in conference. If they have completed and shared their reports in advance of the conference meeting then this should mean they do not need to repeat the information in their report (the ‘detail’). The Conferences need to be a balance of pulling out the pertinent details about risk and existing examples of safety, and creating a multi-agency plan that is likely to keep the child safe. It is not meant to be an opportunity to share an exhaustive bullet point list of what is working well, and what is not.

Scaling, Recommendations and Categories

We use the Signs of Safety model in our conferences. One of the tools within this model is the scaling. We use a ‘Safety scale’ which means when scoring, we are considering how ‘safe’ the child is on a scale of 0-10. 10 is that the child is safe, 0 is that they are not (in very basic terms). The Chair should set the parameters of what 0 means and what 10 means to allow scoring to reflect the needs of the family. Professionals who haven’t yet been to a conference, or other social care meeting, can ask for some guidance around scoring, but there is no prescriptive way of doing this. It is for each professional to weight where they consider the child and situation is.

All professionals attending a conference are expected to scale and to make a recommendation in conference about whether a plan is required, and if a Child Protection Plan is recommended, what category that be under.

Categories can cause some anxiety for families and professionals alike. The four categories are Emotional Abuse, Physical Abuse, Sexual Abuse and Neglect. It’s important that the professionals are honest with their recommendation – if the parent has neglected their child’s needs even if unintentionally or due to their own issues, it is still neglect.

Attendance at Core Group Meetings

If a professional is identified as part of the Core Group of professionals around a child, then they are requested (and expected) to attend regular core group meetings every 6 weeks. Again, the focus of these meetings is ideally to share updates and review the efficacy of the plan, focus on the risk and safety for the children in question. Scaling is expected at the end of CGMs but no recommendation is considered necessary.

Further Reading

London Child Protection Procedures, Core Procedures, CP4

Working Together 2023

Child Sexual Abuse (CSA)

Child sexual abuse is defined in Working Together to safeguard children 2018 as:

‘Involves forcing or enticing a child or young person to take part in sexual activities, not necessarily involving a high level of violence, whether or not the child is aware of what is happening. the activities may involve physical contact, including assault by penetration (for example, rape or oral sex) or non-penetrative acts such as masturbation, kissing, rubbing and touching outside of clothing. They may also include non-contact activities, such as involving children in looking at, or in the production of, sexual images, watching sexual activities, encouraging children to behave in sexually inappropriate ways, or grooming a child in preparation for abuse. Sexual abuse can take place online, and technology can be used to facilitate offline abuse. Sexual abuse is not solely perpetrated by adult males. Women can also commit acts of sexual abuse, as can other children.’

Lewisham Child Sexual Abuse (CSA) Pathway

The Lewisham CSA and therapeutic pathway sets out how professionals should respond to concerns, disclosures, or allegations of Child Sexual Abuse.

Signs and Indicators of Child Sexual Abuse +

All professionals need to be confident they have the knowledge and skills to recognise when children might be showing them that something is wrong.

Children may also drop hints and clues that the abuse is happening without revealing it outright.

Children often do not talk about sexual abuse because they think it is their fault or they have been convinced by their abuser that it is normal or a “special secret”.

Children may also be bribed or threatened by their abuser or told they will not be believed.

A child who is being sexually abused may care for their abuser and worry about getting them into trouble.

Different families may use different words for their genital area which may make a disclosure less obvious. It is therefore important to consider the child’s presentation and following signs when a child is speaking about something that may not be clear.

Emotional and behavioural signs may include:

- Avoiding the abuser – the child may dislike or seem afraid of a particular person and try to avoid spending time alone with them;

- Sexually inappropriate behaviour – children who have been abused may behave in sexually inappropriate ways or use sexually explicit language;

- Changes in behaviour – a child may start being aggressive, withdrawn, clingy, have difficulties sleeping, have regular nightmares or start wetting the bed;

- Changes in their mood – feeling irritable and angry, or anything out of the ordinary;

- Changes in eating habits of developing an eating problem;

- Problems at school – an abused child may have difficulty concentrating and learning, and their grades may start to drop;

- Alcohol or drug misuse; and

- Self-harm.

Physical signs may include:

- Bruises;

- Bleeding, discharge, pains or soreness in their genital or anal area;

- Sexually transmitted infections; and

- Pregnancy

Signs of online sexual abuse may include:

- Spending a lot more or a lot less time than usual online, texting, gaming or using social media;·Being distant, upset or angry after using the internet or texting;

- Being secretive about who they’re talking to and what they’re doing online or on their mobile phone;

- Having lots of new phone numbers, texts or email addresses on their mobile phone, laptop or other device.

The Centre of Expertise on Child Sexual Abuse have designed a CSA signs and indicators template to help professionals to gather the signs and indicators of sexual abuse and build a picture of their concerns.

Definitions of Child Sexual Abuse +

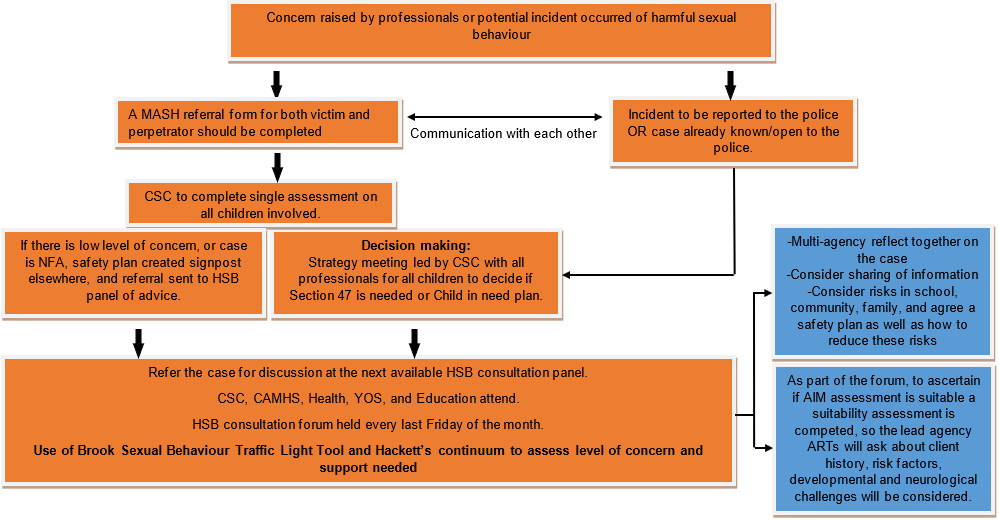

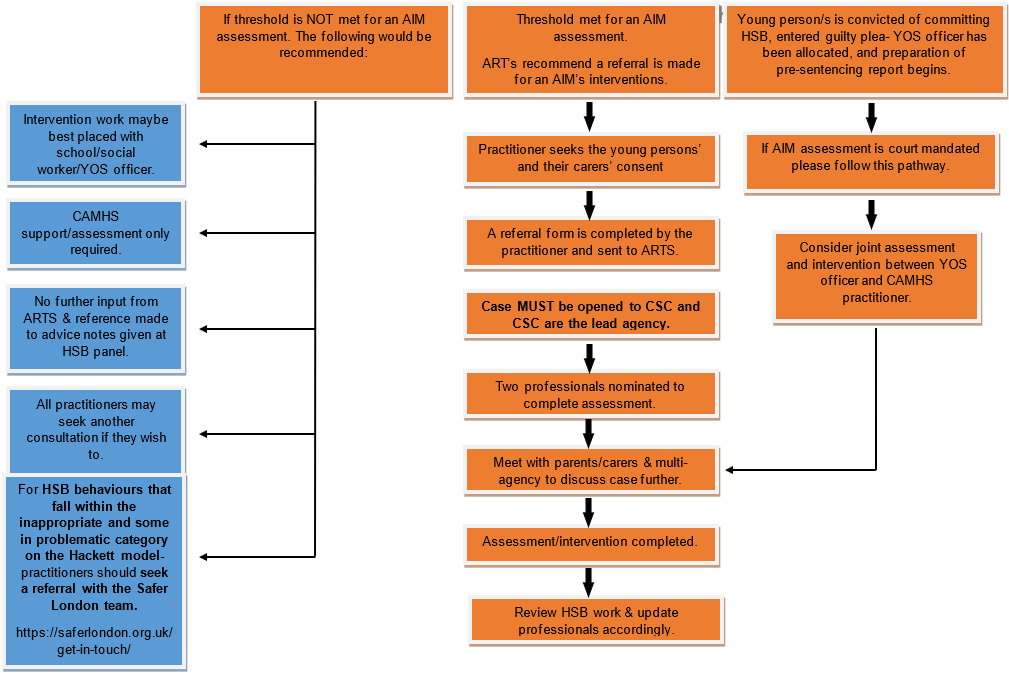

Harmful sexual behaviour (HSB)

Harmful sexual behaviour (HSB) is developmentally inappropriate sexual behaviour which is displayed by children and young people and which may be harmful or abusive (derived from Hackett, 2014). It may also be referred to as sexually harmful behaviour or sexualised behaviour.

HSB encompasses a range of behaviour, which can be displayed towards younger children, peers, older children or adults. It is harmful to the children and young people who display it, as well as the people it is directed towards.’ NSPCC

Signs of HSB

Children and young people demonstrate a range of sexual behaviours as they grow up, and this is not always harmful.

Sexualised behaviour sits on a continuum with five stages:

- Appropriate – the type of sexual behaviour that is considered ‘appropriate’ for a particular child depends on their age and level of development; Inappropriate – this may be displayed in isolated incidents, but is generally consensual and acceptable within a peer group;

- Problematic – this may be socially unexpected, developmentally unusual, and impulsive, but have no element of victimisation;

- Abusive – this often involves manipulation, coercion, or lack of consent;

- Violent – this is very intrusive and may have an element of sadism.

It is not always easy to identify HSB; the NSPCC have created a guide of age-appropriate healthy sexual behaviour that should be considered when assessing whether a child’s behaviour is healthy or harmful: https://learning.nspcc.org.uk/media/1659/responding-harmful-sexual-behaviour.pdf

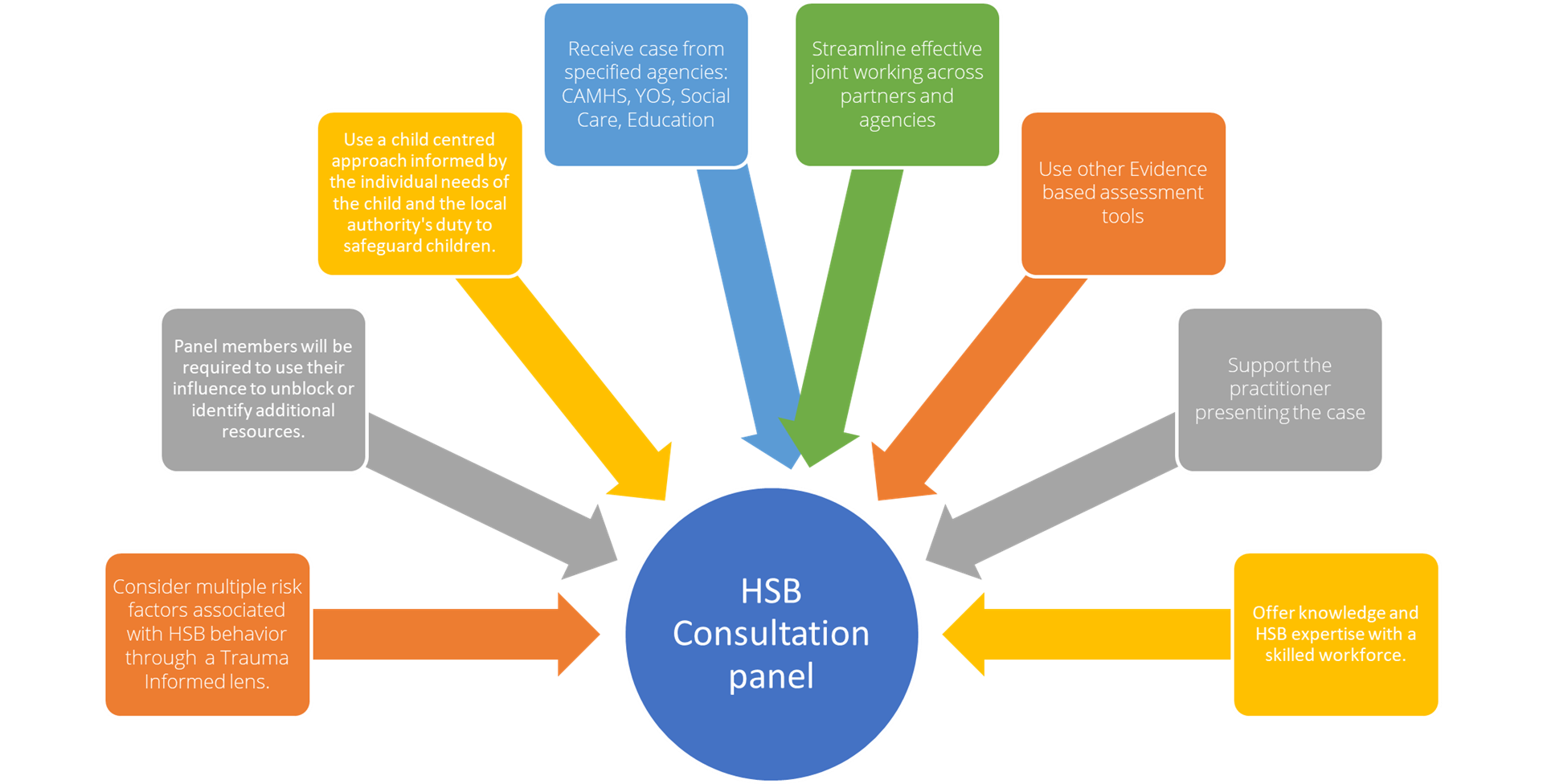

In the borough of Lewisham, multi-agencies aim to work together to provide a specialist service to children and young people who have engaged in harmful sexual behaviour (HSB). This includes harm to other children, young people, and themselves. You can find further information on HSB including the criteria for referrals to the HSB Consultation Panel.

Questions to ask when considering if a child is displaying HSB include

- Is the behaviour unusual for that particular child or young person?

- Have all the children or young people involved freely given consent?

- Are the other children or young people distressed?

- Is there an imbalance of power?

- Is the behaviour excessive, degrading or threatening?

- Is the behaviour occurring in a public or private space?

Child sexual exploitation (CSE) Is defined by the Department of Education as:

‘Child sexual exploitation is a form of child sexual abuse. It occurs where an individual or group takes advantage of an imbalance of power to coerce, manipulate or deceive a child or young person under the age of 18 into sexual activity (a) in exchange for something the victim needs or wants, and/or (b) for the financial advantage or increased status of the perpetrator or facilitator. The victim may have been sexually exploited even if the sexual activity appears consensual. Child sexual exploitation does not always involve physical contact; it can also occur through the use of technology.’

Signs of CSE

Indicators that a child or young person may be being groomed may include:

- Being secretive about who they are talking to and where they are going;

- Often returning home late or staying out all night;

- Sudden changes in their appearance and wearing more revealing clothes;

- Becoming involved in drugs or alcohol, particularly if you suspect they are being supplied by older men or women;

- Becoming emotionally volatile (mood swings are common in all young people, but more severe changes could indicate that something is wrong);

- Using sexual language that you would not expect them to know;

- Premature sexual behaviour in under 16s;

- Engaging less with their usual friends;

- Appearing controlled by their phone; and

- Switching to a new screen when you come near the computer.

Indicators that an adolescent may be being exploited may include:

- Persistently going missing from school or home and/or being found out-of-area;

- Unexplained acquisition of money, clothes, or mobile phones;

- Excessive receipt of texts/ phone calls and/or having multiples handsets;

- Relationships with controlling/ older individuals or groups;

- Leaving home/ care without explanation;

- Suspicion of physical assault/ unexplained injuries including bruising;

- Suffering from sexually transmitted infections/ pregnancy;

- Parental concerns;

- Carrying weapons;

- Significant decline in school results/ performance;

- Gang association or isolation from peers or social networks;

- Becoming estranged from family;

- Self-harm or significant changes in emotional well-being; and

- Volatility in mood/ mood swings.

Types of Child Sexual Abuse +

Child sexual abuse covers a range of illegal sexual activities, divided into two categories – contact and non-contact abuse.

Contact abuse is where an abuser makes physical contact with a child, and it can include:

- Sexual touching of any part of a child, whether clothed or unclothed;

- Using a body part or object to rape or penetrate a child;

- Forcing a child to take part in sexual activities;

- Making a child undress or touch someone else.

Contact abuse can include touching, kissing and oral sex – sexual abuse is not just penetrative.

Non-contact abuse is where a child is abused without being touched by the abuser. This can be done in person or online and can include:

- Exposing or flashing;

- Showing pornography;

- Engaging in any kind of sexual activity in front of a child, including watching pornography;

- Making a child masturbate;

- Forcing a child to make, view or share child abuse images or videos;

- Forcing a child to take part in sexual activities or conversations online or through a smartphone;

- Possessing images of child pornography;

- Taking, downloading, viewing or distributing sexual images of children; and

- Not taking measures to protect a child from witnessing sexual activity or images.

Sexting

Children and young people who are involved in a sexting incident might have:

- Shared an image of themselves;

- Received an image from someone else;

- Shared an image of someone else more widely;

This may have happened with or without consent of all the people involved, and children may have been coerced or pressured into giving consent. It’s a criminal offence to create or share explicit images of a child, even if the person doing it is a child.

Signs of sexting

Sometimes a child might disclose that they have been involved in sexting, or they might mention something which gives cause for concern. Other times, professionals might notice that a child is behaving differently, being bullied, or overhear a conversation and the sexting might come to light when the professional tries to find out what is going on.

Poly-victimisation

Can be defined as the experience of multiple victimisations of different kinds – in different domains of a child’s environment – such as sexual abuse, physical abuse, bullying in school, witnessing community violence or being exposed to family. The emphasis here is on different kinds of victimisation, rather than multiple episodes of the same kind of victimisation. Research suggests that the greater number of victimisations experienced, the greater the impact on children’s mental health and wellbeing. When a child experiences any type of familial maltreatment, the risk for experiencing any other type of abuse or victimisation.

The concept of poly-victimisation raises the possibility of adopting a ‘contextual safeguarding approach’ in relation to intrafamilial child sexual abuse.

Referral of non-recent sexual abuse +

Sometimes an adult may disclose sexual abuse they suffered as a child (which can remain an ongoing traumatic experience), including within public, private, voluntary sectors and family settings. Responses to allegations by an adult of abuse experienced as a child must be at the same high standard of response to current abuse, because:

- There is a significant likelihood that a person who abused a child in the past will have continued and may still be doing so;

- Criminal prosecution may be possible if sufficient evidence can be carefully collated.

The adult who disclosed should be encouraged and supported to report the crime to the Police. If the adult will not report it to the Police, then the worker who the disclosure was made to must make a referral to the Police.

A referral should also be made to Children’s Services where the adult lived as a child and where the perpetrator lives now.

A referral to the Local Authority Designated Officer (LADO) should be made where the perpetrator works with children.

To make a referral to the LADO please email a LADO referral form to LewishamLADO@Lewisham.gov.uk

Additional Support +

Barnardos TIGER – Emotional Support Service

The Barnardos Tiger service offers emotional support for children and young people under 18 years old and up to 25 years old with Special Educational Needs where there has been a disclosure of sexual abuse or sexual assault or where the professional believes sexual abuse is likely.

What is TIGER?

- Short-term intervention; up to 15 sessions

- Evidence & trauma-informed approach

- Co-designed intervention plan, led by young person

- Using coaching to re-empower young person

Support offered in South East London:

- 1:1 meetings for young person

- 1-2 sessions of direct work with parent/carers

- Professional collaboration with team around the child

- Support onward referrals

- Training sessions for professionals

Useful information

T: 07519 294000

E: tigerservices@barnardos.org.uk

(Please note this is not a secure email address and should not be used for referrals)

To make a referral please visit: https://www.barnardos.org.uk/get-support/services/london-spa/tiger-referral

South London CSA Services

The South London CSA Services have produced a series of resources as part of NHS England’s ‘Enhancing sexual abuse pathway for CYP in South London’. These resources are available for all professionals working in the field of CSA within and outside of London.

The books are designed to help children (under 8 and 8-12 years old) and their families develop a shared understanding of what might happen after a child has been sexually abused.

Supporting survivor-practitioners in the workplace

A best practice guide about supporting practitioners with lived experience of sexual harm.

Children & Adolescent Mental Health Services (CAMHS)

Lewisham CAMHS Introduction Video : CAMHS Offer Available to Lewisham Children and Young People

CAMHS Infrastructure

Lewisham Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services (CAMHS) offers therapeutic interventions to children and young people up to the age of 18 who experience mild to serious/complex mental health concerns that impact on daily living.

The service is made up of professionals from different backgrounds working together to provide multi-disciplinary care. This may include:

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatrists

- Clinical Psychologists

- Family Therapists

- Cognitive Behaviour Therapists

- Mental Health Nurses

- Occupational Therapists

- Psychotherapists

- Therapeutic Social Workers

- Child Wellbeing Practitioners

- Educational Well Being Practitioners

Lewisham CAMHS Services Summary and Contact Information

Services are provided at three key community sites within Lewisham Borough:

Kaleidoscope

32 Rushey Green, London, SE6 4JF

Tel: 020 3228 1000 or 020 3228 1001

Lewisham Park

78 Lewisham Park, London, SE13 6QJ

Tel: 020 3228 1001

Holbeach

9 Holbeach, London, SE6 4TW

Tel: 020 8314 9742

If you have any urgent concerns about a child or young person’s mental health or a referral query please contact the team at Kaleidoscope and ask to speak to a staff member on duty.

Tel: 020 3228 1000

Operating hours: Monday to Friday, 9am to 5pm (excluding bank holidays)

Emergencies out of hours: Please advise the parent, or carer to contact the child, or young person’s GP. In an emergency, if it is felt that the child or young person is not able to be kept safe, send them to their local A&E.

Crisis Support Line: South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust operate a telephone support line that is available 24 hours a day if urgent help or advice is needed.

Tel: 0800 731 2864

Services at Kaleidoscope

Lewisham Generic Team (Horizon)

The Kaleidoscope Generic Team (Horizon) offers assessment, treatment and care for children and young people, up to the age of 18, who have significant emotional or mental health difficulties.

Crisis Service

The Child and Adolescent Crisis Service works with children and young people, up to the age of 18, who present at Lewisham University Hospital in crisis. The service also offers follow-up appointments in the community after discharge from hospital.

The Crisis Service also manages duty calls for urgent referrals, and in some cases can offer an appointment on the same day so that the child or young person does not need to attend A&E.

Child and Adolescent ADHD Team (Lewisham)

The Child and Adolescent ADHD Team provides treatment and care for children and young people with Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD), up to the age of 18.

The team also provide guidance and consultation to professionals to discuss potential referrals and consultation to professionals who work with the young people in other settings such as schools.

Neuro-Developmental Team (NDT)

The Neuro-Developmental Team (NDT) offers assessment, treatment and care co-ordination for children and young people, up to the age of 18, with a significant learning disability and/or complex neurodevelopmental disorders.

The Lewisham CAMHS NDT supports children, young people, and their families, who may be experiencing anxieties around their health. The service is for children and young people who have had severe and complex problems for some time.

Child and Adolescent Paediatric Liaison Service

The Paediatric Hospital Liaison Service provides mental health input for children and young people children with acute illnesses, and those with chronic and life-limiting conditions.

The service co-ordinates psychological assessments for children and young people being cared for at University Hospital Lewisham. They can help manage the emotional impact of physical illness on children, young people and families, and improve their ability to manage the illness and its effects.

Child and Adolescent Schools Service (Lewisham)

The Child and Adolescent Schools Service (Lewisham) provides low-intensity, tier 2 assessment, treatment and care for children and young people, from 5 to 18 years old, who have mental health problems.

The service works mainly in Lewisham schools alongside education professionals; however, if necessary, they can offer home visits. Referrals are accepted from the Special Educational Needs and Disability (SEND) panel, New Woodlands School, the Outreach and Inclusion Service, and a small number of targeted schools.

Services at Lewisham Park

SYMBOL Team (Looked After Children)

The Symbol Therapy Team helps young people in local authority care in Lewisham who are struggling with mental health difficulties. The team also provide care for adopted young people living in Lewisham.

Symbol offer assessment, therapeutic intervention and care for young people, up to the age of 18, with moderate to severe emotional, behavioural and mental health problems. The team also offer a low-intensity service for young people leaving the care system, who are moving into adulthood.

The Lewisham Young People’s Service (LYPS)

The Lewisham Young People’s Service (LYPS) provide assessment and treatment for children and young people, up to the age of 18, who have ongoing severe and complex problems for some time that significantly affect their daily life.

LYPS also offers an early intervention service to young people who are experiencing psychosis.

Child and Adolescent Wellbeing Programme (Lewisham)

The Lewisham Children and Young People Wellbeing Practitioners (CWP) Team is a low-intensity, tier 2 service for children and young people who may not meet the threshold for mainstream CAMHS teams.

The CWP team provide short-term, low intensity, evidence-based, guided self-help interventions for children, young people and their parents. Treatment is available for mild to moderate anxiety, low mood, or mild behavioural difficulties.

Services at Holbeach

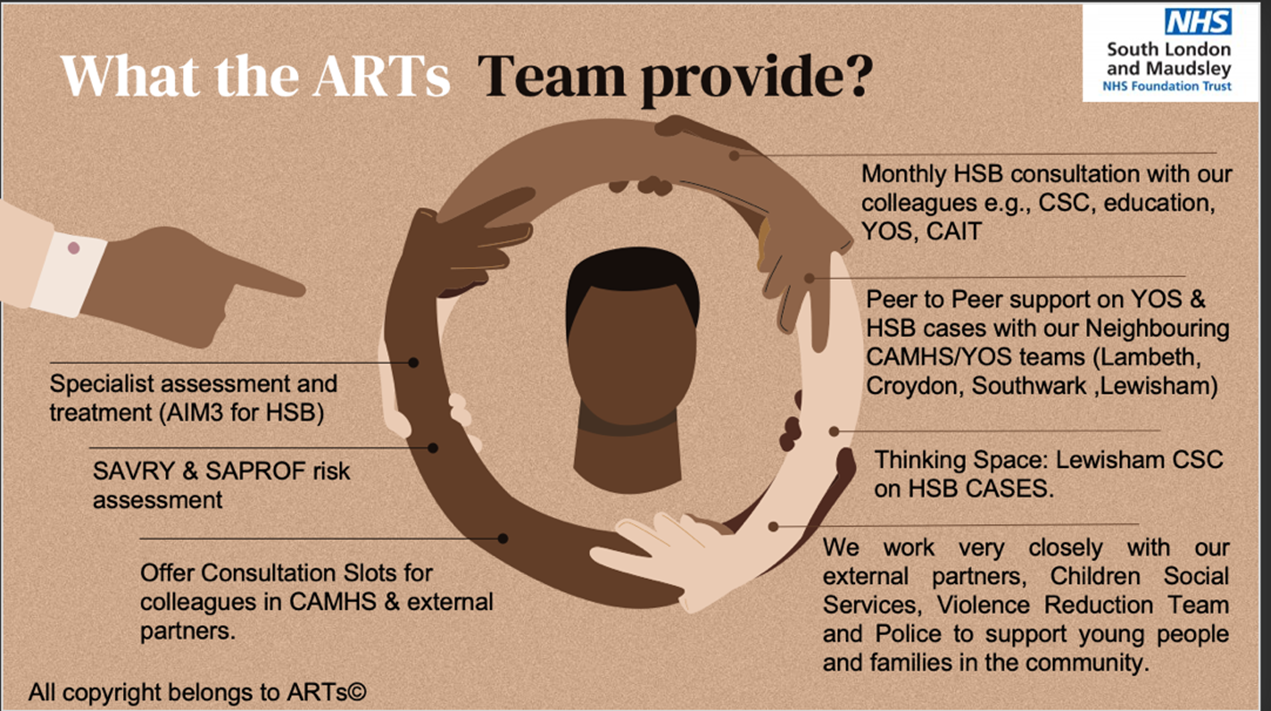

Adolescent Resource and Therapy Service (ARTS)

The Adolescent Resources and Therapy Service (ARTS) provide assessment, treatment and care for young people, up to the age of 18, who are known to a Youth Offending Service (YOS).

The ARTS team provide one to one and group treatment and care, and work with the police, the public protection unit, social services and our local Multi-Agency Public Protection Arrangement (MAPPA) team to support people in the community. The team also work with children and young people who exhibit sexually inappropriate behaviour.

Referrals

Please consult the CAMHS Referral Criteria for full information on services and referrals.

When making a referral to Lewisham CAMHS please use our CAMHS Referral Form

Non urgent referrals for CAMHS teams based at Kaleidoscope can be emailed to: LewishamCAMHSAdmin@slam.nhs.uk

Useful links

Young Minds - children’s mental health charity, which offers a host of advice and resources

Kooth - free online service that offers emotional and mental health support for children and young people

Samaritans - Charity aimed at providing emotional support to anyone in emotional distress

MindEd - free educational resource on children and young people’s mental health for adults

Royal College of Psychiatrists - Professional medical body responsible for supporting psychiatrists

Domestic Abuse & MARAC

Domestic abuse is defined as “any incident or pattern of incidents of controlling, coercive, threatening behaviour, violence or abuse between those aged 16 or over who are, or have been, intimate partners or family members regardless of gender or sexuality”. The abuse can encompass, but is not limited to:

- psychological

- physical

- sexual

- financial

- emotional

Domestic abuse can also include forced marriage and so-called “honour crimes”.

Controlling and coercive behaviour

Domestic abuse is often thought of as physical, such as hitting, slapping or beating, but it can also be controlling or coercive behaviour. This is important as what might look like an isolated incident of violent abuse could be taking place in a context of controlling or coercive behaviour.

Controlling behaviour is a range of acts designed to make a person subordinate and/or independent by isolating them from sources of support, exploiting their resources and capacities for personal gain, depriving them of the means needed for independence, resistance and escape and regulating their everyday behaviour.

Coercive behaviour is an act or a pattern of acts of assault, threats, humiliation and intimidation or other abuse that is used to harm, punish, or frighten their victim.

We know that the first incident reported to the police or other agencies is rarely the first incident to occur; often people have been subject to violence and abuse on multiple occasions before they seek help.

Learning resources to support health and social work in situations of coercive control

A set of learning resources for social workers, safeguarding leads, and health and social care practitioners, provides information and guidance on how to recognise and respond to coercive and controlling behaviour in intimate or family relationships.

Supporting the non-abusing parent in a holistic way that acknowledges the impacts of coercive control is important in achieving good outcomes for children. Research showed that children also experience the impacts of coercive control of a parent; for example, becoming isolated from family and friends, finding it difficult to gain independence, and feeling disempowered. The resources, which include five detailed case studies, will support practitioners to improve their understanding of the dynamics of power and control that underpin domestic abuse, enabling them to build trusting relationships with children and survivors.

The examples, tools and videos bring together evidence from research, practitioner experience, and the voice of people using services, to enable professionals to put the law into practice and improve support for people who are experiencing coercive control.

The Chief Social Worker’s Office at the Department of Health commissioned the materials, which were developed by Research in Practice for Adults and Women’s Aid. http://coercivecontrol.ripfa.org.uk/

Safeguarding children exposed to domestic abuse

Children who live in families where there is domestic abuse can suffer serious long-term emotional and psychological effects. Even if they are not physically harmed or do not witness acts of violence, they can pick up on the tensions and harmful interactions between adults. Children of any age are affected by domestic violence and abuse. At no age will they be unaffected by what is happening, even when they are in the womb.

The physical, psychological and emotional effects of domestic violence on children can be severe and long-lasting. Some children may become withdrawn and find it difficult to communicate. Others may act out the aggression they have witnessed, or blame themselves for the abuse. All children living with abuse are under stress.

Professionals should:

- Consider the presence of domestic abuse as an indicator of the need to assess a child’s need for support and protection

Safe Lives, a national domestic abuse charity, has created a toolkit practitioners and front-line workers can use to identify high risk cases of domestic abuse, stalking and ‘honour’-based violence. The purpose of the checklist is to give a consistent and simple-to-use tool to practitioners who work with victims of domestic abuse in order to help them identify those who are at high risk of harm and whose cases should be referred to a MARAC meeting in order to manage the risk.

The toolkit has been endorsed by agencies such as the police (Association of Chief Police Officers), National Centre for Domestic Violence, and CAFCASS, who believe that the primary audience should be front line practitioners working with victims of domestic abuse who are represented at MARAC. This will include both domestic abuse specialists such as IDVAs and generic practitioners such as those working in a primary care health service or housing.

Locally, both the Adult’s Safeguarding Board and Children’s Safeguarding Partnership (LSAB / LSCP), as well as the Safer Lewisham Partnership (SLP) have agreed that all agencies in Lewisham working with, or supporting families at risk of domestic violence are expected to use the risk checklist. This is vitally important because using an evidence based risk identification tool increases the likelihood of the victim being responded to appropriately and therefore, of addressing the risks they face. The risk checklist gives practitioners common criteria and a common language of risk.

Safe Lives have produced an updated version of the RIC, which now includes comprehensive guidance explaining each risk question, how they can be asked, as well as practice points. There is also a frequently asked questions page with some useful tips on the checklist. The Safe Lives website has helpful resources about other ways your agency may access support, training or download the checklist in other languages. The Lewisham Safeguarding Children’s Partnership also offers training on the use of the checklist which is free for all professionals in the borough to attend, however, for more questions about the use of the RIC, access to training, and questions about domestic violence MARAC process, please visit www.lewisham.gov.uk/vawg or contact the Violence Against Women & Girls (VAWG) Programme Manager on vawg@lewisham.gov.uk

Safeguarding high-risk victims of domestic violence and abuse – referring to the MARAC

The Lewisham Domestic Violence Multi-Agency Risk Assessment Conference (MARAC) is a risk management meeting where professionals share information on high and very high risk cases of domestic violence or abuse and put in place a risk management plan. The aim of the meeting is to address the safety of the victim, children and agency staff and to review and co-ordinate service provision in high risk domestic violence cases.

To be referred to the MARAC the individual must reside in the London Borough of Lewisham, be over the age of 16, be currently experiencing domestic violence or abuse (according to the cross Government definition of domestic violence)[1] and be assessed as being at high or very high risk of harm of domestic violence or abuse in accordance with the Lewisham MARAC referral risk criteria. In order to assess whether a case meets the risk threshold, the Safe Lives DASH MARAC risk indicator checklist should be completed by the referring agency.

A tailored action plan will be developed at the MARAC to reduce the risk to the victim, children, other vulnerable parties and any staff and to ensure that the risk the perpetrator presents is managed appropriately. Examples of actions that will be agreed include flagging and tagging of files, referral to other appropriate multi-agency meetings, prioritising of agencies’ resources to MARAC cases.

Any service agency signed up to the MARAC Information Sharing Protocol may refer a case to the MARAC using the Lewisham MARAC Referral Form, and all agencies should be actively screening for domestic violence or abuse. Referrals should be submitted to each agency’s MARAC representative. Please contact your line manager to find out who your agency’s MARAC representative is.

For more questions about the use of the MARAC, access to training, and questions about the process, please visit www.lewisham.gov.uk/vawg or contact the Violence Against Women & Girls (VAWG) Programme Manager on vawg@lewisham.gov.uk , or the MARAC Coordinator on dvmarac@lewisham.gov.uk

[1] https://www.gov.uk/guidance/domestic-violence-and-abuse

For further information

Letter to partners on the use of the DV risk assessment

visit www.saferlondon.co.uk/safer-lewisham

See the Domestic Violence information in our practice procedures

Useful Links:

Resources: http://imkaan.org.uk/resources

MOPAC VAWG Strategy 2018-2021

MOPAC Domestic and Sexual Violence Dashboard

Home Office Resources for Violence Against Women & Girls (VAWG)

Galop - The LGBT Anti-Violence Charity

Services Available to Lewisham Residents

Refuge, The Athena Service

The Athena service, run by Refuge provides confidential, non-judgmental support to those living in the London Borough of Lewisham who are experiencing gender-based violence. It opened its doors in April 2015 and provides outreach programmes, independent advocacy, group support, refuge accommodation and a specialist service for young women.

It provides the following services, all under one roof:

- One-to-one confidential, non-judgmental, independent support

- A specialist independent gender-based violence advocacy (IGVA) team to support clients at risk of serious harm

- A specialist service for 13-19 year-old girls

- Group support

- A peer support scheme to help break isolation; build social networks and provide support clients regain control of their lives

- Volunteering opportunities

Telephone: Athena Service on 0800 112 4052

Email: lewishamvawg@refuge.org.uk

Website: https://www.refuge.org.uk/our-work/our-services/one-stop-shop-services/athena/

African Advocacy Foundation

A community-led organisation working to promote better access to health, education and other opportunities for disadvantaged communities in the UK, Europe and parts of Africa.

African Advocacy provide practical support, policy work, advocacy, information, guidance and training to professionals and community members alike. African advocacy work to empower individuals and families experiencing multiple disadvantages and barriers including ill health, poverty, deprivation, violence, isolation and those relating to language, culture, faith and other social issues.

Location:

CATFORD (MAIN) OFFICES:

76 Elmer Road, Catford, London SE6 2ER

Telephone:

0208 698 4473

Website: https://www.africadvocacy.org/

BelEve UK

The purpose is to equip girls and young women with the right support, skills and confidence to make informed choices about their future; improve their educational, social and economic outcomes whilst taking control of their lives.

Location:

The Albany, Deptford, SE8 4AQ

Telephone:

0203 372 5779

Website: https://beleveuk.org/

Latin American Women’s Rights Service (LAWRS)

LAWRS has a zero tolerance policy of any form of Violence against Women and Girls (VAWG). Our team offers advice, advocacy and practical support to Latin American women who are experiencing or have experienced Domestic Violence, Harmful practices or any other form of violence.

Location:

Tindlemanor, 52-54 Featherstone Street.

London, EC1Y 8RT

Telephone:

020 7336 0888, 084 4264 0682

Website: http://www.lawrs.org.uk/

IKWRO – Women’s Rights Organisation

IKWRO are committed to providing non-judgmental support to women who speak Kurdish, Arabic, Turkish, Farsi, Dari, Pashtu and English.

Location:

IKWRO – Women’s Rights Organisation

PO Box 75229

LONDON

E15 9FX

Telephone:

0207 920 6460

Website: http://ikwro.org.uk/

Women and Girls Network (WGN)

WGN is a free, women-only service providing a holistic response to women and girls who have experienced, or are at risk of, gendered violence.

Telephone:

0808 801 0660

Website: http://www.wgn.org.uk/

WE Women (Women Empowering Women)

We Women is a collaboration of women which has been delivering community support to women since March 2017. In August 2018, we women became a constituted community group.

We Women are entirely volunteer run, and our aims are to:

- Empower women to be more self-sufficient

- Improve women’s health & well-being

- Address the material impacts of poverty within the local community

Location:

Pepys Resource Centre Old Library Deptford Strand London

London

Greater London

SE8 3BA

United Kingdom

Telephone:

020 8691 3146

Website: https://www.lewishamlocal.com/places/united-kingdom/greater-london/london/lewisham-groups/we-women-women-empowering-women/

Early Years Alliance - Lewisham Children's and Family Centres

The Alliance is working together with Clyde Nursery School, Beecroft Garden School and Kelvin Grove/Eliot Bank and Downderry Children’s Centres to deliver a clear seamless borough wide children’s centre offer for families in the London Borough of Lewisham, working alongside health visiting, midwifery, schools and public health services.

Lewisham Children and Family Centres offer families access to a range of health, education, play, parenting, adult education, employment support and family support services right across the borough.

Website: https://www.lewishamcfc.org.uk/

National Stalking Helpline – Suzy Lamplugh Trust

The National Stalking Helpline is run by Suzy Lamplugh Trust. Their mission is to reduce the risk of violence and aggression through campaigning, education and support.

Telephone: 0808 802 0300

Website: https://www.suzylamplugh.org/

METRO

METRO is a leading equality and diversity charity providing health, community and youth services across London and the south-east, with some national and international projects. METRO promotes health, wellbeing and equality through youth services, mental health services and sexual health and HIV services and works with anyone experiencing issues related to gender, sexuality, diversity or identity.

Location: 141 GREENWICH HIGH ROAD, GREENWICH, SE10 8JA

Telephone: 020 8305 5000

Website: https://metrocharity.org.uk/

RASASC - Rape & Sexual Abuse Support Centre Rape Crisis South London

RASAC believe too many women have had to be silent for too long about the violence perpetrated against them.

They understand that it can be difficult to speak up, hard to find the words or to believe that anyone will listen.

RASAC will listen. They believe. They will stand up alongside you. You do not have to do this alone.

Telephone: 0808 802 9999

Postal Address:

PO BOX 383, Croydon, CR9 2AW

Website: http://www.rasasc.org.uk/contact/

Stonewall

Information and campaigning for LGBT rights. Got a question? A problem? Need support? Stone wall are here to help with any issues affecting LGBT people or their families. Whatever your situation, you’re not on your own. Stonewall will do what they can to help or point you in the right direction to someone who can.

Telephone: 0800 0502020

Write to Stonewall: Stonewall 192 St. John Street London EC1V 4JY

Website: https://www.stonewall.org.uk/help-advice/contact-stonewalls-information-service

Respect

Men and women working together to end domestic violence

Telephone: 0808 802 4040

Address: The Green House

244-254 Cambridge Heath Road

London

E2 9DA

Website: http://respect.uk.net/

The Deaf Health Charity – Sign Health

www.signhealth.org.uk/our-projects/deafhope-projects/

Text: 07970350366

Rights of women

www.rightsofwomen.org.uk

Respect Helpline for men

0808 8010327

www.respectphoneline.org.uk/help-for-domestic-abuse-victims

Women's Aid live chat

This is an online chatting service which is ideal for victims who are self-isolating and do not want to be heard.

www.chat.womensaid.org.uk

www.womensaid.org.uk

0117 944 44 11

NSPCC Helpline - 0800 028 3550 or fgmhelp@nspcc.org.uk

GALOP National LGBT+ Domestic Abuse Helpline

0800 999 5428

www.galop.org.uk/domesticabuse

Difficult conversations with parents / carers

A guide for practitioners who work with children and their families.

The information in this guide is not exhaustive and it should be used as a reference alongside practitioners own safeguarding practices and in conjunction with appropriate supervision.

Four factors to consider when preparing for a difficult conversation with a parent or carer:

- Principles – that underpin safeguarding children.

- Planning – how to plan or be prepared

- The Conversation – things to consider when having a conversation

- Examples – open questions and suggestions

1. Principles – to support safeguarding discussions with parents / carers

- Always take time to plan the conversation before you speak to parents.

- Be open and honest, use basic language, avoid jargon.

- Ensure child protection policies are clear.

- Include child protection issues in information you give out to parents you are working with.

- Explain your statutory duty to safeguard children’s welfare, “duty of care” and requirement to report your concerns.

- Ensure parents / carers sign to acknowledge they have read and understood your safeguarding policy and offer them a copy.

- Use Early Help, refer to a children’s centre, or signpost to other support agencies, i.e. health visitor, parenting courses etc.

2. Planning

If you feel it’s too risky to talk to parents before speaking to Children’s Social Care, then don’t. Do not put yourself or a child at risk, e.g. if:-

- There is suspected sexual abuse.

- Parents could destroy evidence or hinder a police investigation.

- It is possible the child could be silenced.

Otherwise it’s good practice to discuss concerns with parents/carers and tell them you are going to make a referral. Before your conversation:-

- Plan how you are going to broach your concern and how to respond to different responses, e.g. anger, denial, emotional breakdown etc.

- Choose a time and place to give full privacy.

- Consider the timing of the meeting (e.g. a tired, crying baby, or collecting other children from school etc.) depending on the urgency of the concern.

- Adapt your style to the parent, consider language barriers or learning difficulties.

- Acknowledge your own anxiety about dealing with a difficult situation as it may affect your communication style.

- Have the child’s key worker with you or nearby for support and as a witness (and vice versa) or get support from Children’s Social Care.

- If previous experience of the parent/carer suggests they may pose a risk, make a full risk assessment and do not meet alone.

3. The Conversation

Make sure members of staff know where you are and what you are doing before a meeting. Tips and ideas for having a difficult conversation:-

- Consider your position in the room so nobody feels trapped.

- Ensure children cannot overhear you and are occupied (provide toys etc.)

- Frame the concern in a model of help and support.

- Be straight forward – Tell the parent/carer a referral to the Multi-Agency Safeguarding Hub is going to be or has been made.

- Tell them that “as a parent/carer they will want to get to the bottom of the matter”.

- Give clear explanations.

- Always remain confidential and professional.

- Words are sometimes really hard to find when approaching a parent – use ‘active listening’.

- Do not argue, interrupt, give advice, pass judgement, jump to conclusions or let the parent’s sentiment affect you.

- Avoid excessive reassurance, it may not be all right.

- Do encourage the parent to talk.

- Clarify what the parent means.

- Summarise what the parent has said.

- Consider your communication style: tone, pitch, speed of voice, body language (body slightly to the side, with an open stance or sit) be clam, make eye contact and appreciate they may need to talk.

- Consider the parents point of view which may be influenced by; bad experience of services, lack of trust, limited or distorted understanding of what is appropriate for children, learning difficulties, cultural and language barriers.

- Explain the nature of your concern using tact and diplomacy, but be direct and use factual information “Jodie was not brought to the last 2 appointments, what is the reason for this?”

- Do not use words such as child protection or child abuse, try words such as concerns, welfare, and duty of care.

Use your eyes and ears more than your mouth.

4. Examples

This is not an exhaustive list and you may want to use a technique of your own, following the general principle of open and probing questions:

- Avoid using “I think” which indicates it could be your own opinion.

- Avoid using jargon, try:-

- “I need to talk to you about the injury to XY’s face, can you tell me what happened?”

- “XY has been very lethargic today and says he has not slept, is there anything going on that might be troubling him?”

- “XY’s behaviour has changed dramatically over the last few weeks, (s)he has gone from being a happy, outgoing child to a very quiet, withdrawn child. Have you any idea what could have caused this?”

- “Whenever there is a worry about any child, or they something about being hurt we legally have to pass on that information to children’s services – you may have read this in the parent’s information/handbook when XY started?”

- “XY told a member of staff he is slapped every night, and, because of what he has said I have informed Children’s Social Care. All settings are expected to talk to Children’s Social Care when children say things like this, and Children’s Social Care have asked me to talk to you about this. Can you tell me what happened?”

Questions can start with the following:-

- “is there any reason why……….”

- “we need to have a chat………..”

- “XY has said……………………..”

- “I have noticed XY has seemed hungry in the mornings, is (s)he managing to have breakfast before he comes to school?”

- XY has a bruise on his face but he can’t remember how it happened, do you know how he did it?”

Next steps?

Once you have had a conversation or a series of discussions with the parent or carer, you may need to consider what actions, if any, you need to take. Consider the following:-

- Professional curiosity – have you confirmed the response you have received from other agencies? Do you need to make further enquiries?

- Trust your instincts – You have spoken to the parent/carer and you know the child – trust your instincts if you still have concerns.

- Follow safeguarding procedures – ensure you check your agency safeguarding procedures and seek guidance from an appropriate person.

- Pre and Post Supervision – agencies have varying supervision procedures; be sure to raise your concerns and get guidance and support before and after you have had a conversation with a parent/carer as this will give you a chance to reflect on what happened and discuss what needs to happen next (reflective practice).

- Escalation – If you are still concerned about a decision or practice you can escalate your concerns; the LSCP recommend you follow our Resolving Professional Differences / Escalation Policy.

- Referral – Following any discussion, if you are concerned about the safety of a child or you believe they are at risk of immediate danger – contact the police. If you believe the child is at risk of significant harm – seek guidance from the MASH team.

- Early Help – You may want to contact Early Help or create a Team Around the Family.

| What are we worried about? |

What’s working well? |

What needs to happen? |

|

What words would you use to talk about this problem so that parents/carers understand?

Use plain language and avoid jargon.

Consider any problems the family might be having which are making this problem harder to deal with e.g. housing, finances, isolation, or family breakdown.

Example questions:-

- I need to talk to you about the mark XY’s face, (s)he can’t remember how it happened, and do you know how (s)he did this?

- XY’s behaviour has changed a lot in the last few weeks. (S)he has gone from being happy and outgoing to quiet and withdrawn – have you any idea what might have caused this this?

- We are having a lot of problems with XY, (s)he seems angry. Is there anything happening at home which would help us to understand this?

- I know we have talked about this before but I am still worried because XY is still quite dirty when she comes to school and other children have commented that (s)he smells. Do you have everything you need at home to wash clothes and to have a bath regularly?

|

Who are the people who care for the child? And what are the best things about how they care for them?

Who would the child say are the most important people in their lives? And how do they help them grow up well?

Example questions:-

- It sounds like things are a bit difficult at the moment, is anyone supporting you?

- What would XY say are the best things about his life?

- You have been doing well to get XY to school with all that is happening, is there anything we can do to support you further?

- Have you noticed this problem before? How was it sorted out in the past?

|

Now you have explored this more, how worried are you about this child? 10 is not worried; 0 is so worried you need to make a referral for support or safeguarding.

- What would you need to see for it to be 10?

- What do you think is the next step to getting this worry sorted out?

- Have you done any direct work with the child?

Next steps:

- Curiosity – verify any information with professionals or other family members.

- Supervision – seek guidance before and after interaction with parents/carers to reflect on the information gathered.

- Procedures – follow your agency safeguarding procedures.

- Referral – If you are concerned about the safety of the child or young person.

- Escalation – If you are not satisfied with the outcome of the referral and still have concerns.

|

Discharge & Safety Planning Protocol for Lewisham Children & Young People

For Children and Young People who present and require a multi-agency response to address

their safeguarding and mental health needs)

July 2022

Partners to the Protocol

- Lewisham and Greenwich NHS Trust

- London Borough Lewisham, Lewisham Children’s Social Care

- South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trus

Purpose and Scope

The purpose of this protocol is to support multi-agency practitioners to make appropriate arrangements which support the safe and timely discharge of children and young people under 18 years of age.

The protocol is intended to ensure that all practitioners are clear about the steps to take to ensure that no child is discharged from hospital into an unsafe environment, where their health or well-being may be compromised or where further significant harm could occur.

The protocol applies to children and young people who require a multi-agency response to address their needs. A multi-agency response may be required due to:

- Serious or complex mental health needs requiring hospital admission;

- Self-harm or attempted suicide; or have expressed an intention to do either;

- Safeguarding and other welfare concerns cover situations where there is known or suspected neglect or abuse;

- Exploitation or neglect is known prior to admission, and this is recent or current, it would be expected that these children have an allocated social worker);

- The child/young person is looked after;

- Abuse, exploitation or neglect comes to light or is suspected during the hospital admission, Children subjected to Trafficking/FGM/ Modern Slavery;

- Ward Staff raise concerns about the parent/child interaction, Parent/Carer whose understanding or concern for their child is lacking. Children or young people in Police custody or due to be arrested upon discharge.

- Children or young people who have been the victim of physical or sexual assault;

- The Child/Young Person says they do not want to return home;

- This is not an exhaustive list and professionals should apply their professional judgement and consult with their named safeguarding leads if they have any concerns at all about a child/young person.

Principles

Any child or young person, who self-harms or expresses thoughts of self-harm or suicide, must be taken seriously and appropriate help and intervention, should be offered at the earliest point. Any practitioner, who is made aware that a child or young person has self-harmed, or is contemplating this or suicide, should talk with the child or young person without delay.

Most children who have been admitted with mental health needs will need on-going community care for a period of time after discharge. Follow up services for the young person’s mental health services could include, outreach sessions, liaison with local services, and outpatient therapy sessions and will be determined by the local CAMHS service following assessment.

Discharge planning is an essential part of care management in any hospital setting. It ensures that health and social care systems are proactive in supporting individuals and their families in the community. It needs to start early to anticipate problems, put appropriate support in place and agree service provision. Consideration should be given to the wider environment the child will be returning to, including siblings and other members of the household.

Children should not remain in hospital once they are well enough to leave. However, it is essential that when a child is in hospital and there are safeguarding concerns about the child, effective multi-agency planning between key professionals working with the child is undertaken before the child is discharged from hospital. Where there are safeguarding concerns, a referral must be made to Lewisham Children’s Social Care.

All agencies have a duty to share information and a joint responsibility to work together to protect children and promote their wellbeing and safety. Referrals to Lewisham Children’s Social Care must be made to MASH service who will determine the level of response by processing information through the multi-agency safeguarding hub.

Linked Policies and Procedures

The protocol should be read in conjunction with:

- The London Child Protection Procedures

- LGT Safeguarding Guideline for Paediatricians Algorithm for Safeguarding

- LGT Safeguarding Children & Young People Policy

The Full Protocol Content

Lewisham Discharge Protocol for Children and Young People - July 2022

Emotional Abuse of Children & Young People

Working Together 2018 Definition

The persistent emotional maltreatment of a child such as to cause severe and persistent adverse effects on the child’s emotional development.

It may involve, include, or be conveyed to a child:-

- They are worthless or unloved.

- Inadequate.

- Valued only insofar as they meet the needs of another person.

- Not giving the child opportunities to express their views, deliberately silencing them or “making fun” of what they say or how they communicate.